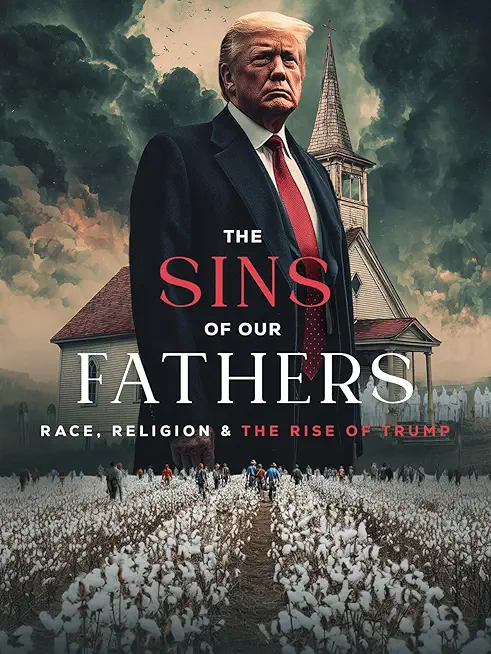

The Sins of our Fathers:

Race, Religion and the Rise of Trump

A Documentary Film by Matthew Pridgen

If you are looking for a film that makes you feel great about America, this is not the film for you. If you are looking for a film that makes you feel great about the Christian faith, this is not the film for you. If you have been wondering why Evangelical Christians are the biggest voting block that continues to support Donald Trump no matter what he does, this is the film for you.

The film is set in Charleston, S.C., “The Holy City” with a skyline dominated by church steeples, the city where the American Civil War began. The film begins with a question: “Did you vote for him in 2016?” Matthew Pridgen, the writer of the film, responds: “Yes, I did,”

We learn from statements on the screen that Matthew is a White, Evangelical Christian that grew up in Charleston, in the affluent area known as “south of Broad” (street).

“So yea, I’m one of those 81 percent of Evangelicals who voted for Trump in 2016” Mattthew continues. “Why did you vote for him?” asks the interviewer. “I didn’t know anything about him, really. I was a life long Republican and he was the Republican nominee. And at that time I was voting pretty much solely on the abortion issue.” “Did you vote for him again in 2020 or 2024?” “No” Matthew replied, shaking his head.” “What happened?” “The East Side happened.”

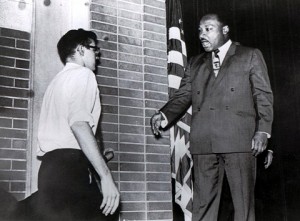

We are set up for the conflict by video footage of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. giving his speech, “The Other America.” The two Americas Dr. King spoke about in that speech stand side-by-side in Charleston. The affluent live South of Broad, in mansions that are viewed by hundreds of tourists each year. The poor, mostly black population lives on the East Side, in housing dating back to the days of slavery. During his college years Matthew got involved in drugs. After taking 27 hits of LSD he tried to drown himself in the ocean. “And I met Jesus, on an 18 hour swim in the Atlantic Ocean.” After that experience, Matthew developed “a heart for the homeless . . . that’s how I got to the East Side.”

The film moves back and forth between Matthew, sitting in his lavish home and pictures of the East Side. It tells the familiar history of race relations in the South: slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crowe, the Civil Rights Movement, desegregation of the public schools. In each case, Southern Christianity used the Bible to sanction, justify, and promote the superiority of the white race.

“Religion is a powerful thing,” says Rev. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove in the film. “People who have tried to maintain control throughout the history of the world have used religion to keep people together around their agenda, and that is part of the American story that we can’t overlook.” The film makes clear, after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 produced a number of counter movements, all intended to maintain white control. Here is where the film is most enlightening. Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs disproportionately targeted black communities, resulting in mass incarceration of black males. The Moral Majority appealed to white Southern Christians with its emphasis on traditional values, morality, and culture—all of which helped maintain white control. Ronald Reagan’s famous line, “Government doesn’t solve problems, government is the problem” echoed southern dissatisfaction with what they saw as government overreach in both emancipation and desegregation. All these movements culminated in the rise of Donald Trump, who used both religion and white supremacy to maintain power.

Rev. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove offers an alternative to the religion based on race and control. “God gives us a very different way of bringing righteousness, bringing justice into the world. It’s not through force but through the power of love. And I think confronting this abuse and distortion of faith is an opportunity to relearn those core messages of the Biblical story.”

In the last ten minutes of the movie each of the main characters who were interviewed echo this same message in one way or the other. But if there is a criticism to be made, it is that ten minutes of hope in a 90-minute film is insufficient. I left the movie mostly discouraged by this long, evil history of Evangelical Christianity in America. It is an incredible act of faith to believe and hope that love can overcome such darkness.

The film concludes with singer Ann Caldwell singing a traditional African song. The lyrics are chilling:

“Lord, how come me here? I wish I had never been born.

There ain’t no freedom here, Lord I wish I had never been born.

They treat me so mean here, Lord I wish I had never been born.

They sold my children away, Lord I wish I had never been born.”

The film is set in Charleston, S.C., “The Holy City” with a skyline dominated by church steeples, the city where the American Civil War began. The film begins with a question: “Did you vote for him in 2016?” Matthew Pridgen, the writer of the film, responds: “Yes, I did,”

We learn from statements on the screen that Matthew is a White, Evangelical Christian that grew up in Charleston, in the affluent area known as “south of Broad” (street).

“So yea, I’m one of those 81 percent of Evangelicals who voted for Trump in 2016” Mattthew continues. “Why did you vote for him?” asks the interviewer. “I didn’t know anything about him, really. I was a life long Republican and he was the Republican nominee. And at that time I was voting pretty much solely on the abortion issue.” “Did you vote for him again in 2020 or 2024?” “No” Matthew replied, shaking his head.” “What happened?” “The East Side happened.”

We are set up for the conflict by video footage of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. giving his speech, “The Other America.” The two Americas Dr. King spoke about in that speech stand side-by-side in Charleston. The affluent live South of Broad, in mansions that are viewed by hundreds of tourists each year. The poor, mostly black population lives on the East Side, in housing dating back to the days of slavery. During his college years Matthew got involved in drugs. After taking 27 hits of LSD he tried to drown himself in the ocean. “And I met Jesus, on an 18 hour swim in the Atlantic Ocean.” After that experience, Matthew developed “a heart for the homeless . . . that’s how I got to the East Side.”

The film moves back and forth between Matthew, sitting in his lavish home and pictures of the East Side. It tells the familiar history of race relations in the South: slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crowe, the Civil Rights Movement, desegregation of the public schools. In each case, Southern Christianity used the Bible to sanction, justify, and promote the superiority of the white race.

“Religion is a powerful thing,” says Rev. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove in the film. “People who have tried to maintain control throughout the history of the world have used religion to keep people together around their agenda, and that is part of the American story that we can’t overlook.” The film makes clear, after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 produced a number of counter movements, all intended to maintain white control. Here is where the film is most enlightening. Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs disproportionately targeted black communities, resulting in mass incarceration of black males. The Moral Majority appealed to white Southern Christians with its emphasis on traditional values, morality, and culture—all of which helped maintain white control. Ronald Reagan’s famous line, “Government doesn’t solve problems, government is the problem” echoed southern dissatisfaction with what they saw as government overreach in both emancipation and desegregation. All these movements culminated in the rise of Donald Trump, who used both religion and white supremacy to maintain power.

Rev. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove offers an alternative to the religion based on race and control. “God gives us a very different way of bringing righteousness, bringing justice into the world. It’s not through force but through the power of love. And I think confronting this abuse and distortion of faith is an opportunity to relearn those core messages of the Biblical story.”

In the last ten minutes of the movie each of the main characters who were interviewed echo this same message in one way or the other. But if there is a criticism to be made, it is that ten minutes of hope in a 90-minute film is insufficient. I left the movie mostly discouraged by this long, evil history of Evangelical Christianity in America. It is an incredible act of faith to believe and hope that love can overcome such darkness.

The film concludes with singer Ann Caldwell singing a traditional African song. The lyrics are chilling:

“Lord, how come me here? I wish I had never been born.

There ain’t no freedom here, Lord I wish I had never been born.

They treat me so mean here, Lord I wish I had never been born.

They sold my children away, Lord I wish I had never been born.”