DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream . . . I have a dream that one day in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. ”

In late 1967 Grosse Pointe was a troubled community. The race riots in neighboring Detroit in July of that year and the resulting fear and tension were still fresh in everybody’s mind. The riots– there were several across the city, lasting for almost a week– resolved nothing. Racial tension remained high in both Detroit and Grosse Pointe, the Motor City’s most exclusive suburb.

It was not surprising then that there was mixed reaction to the announcement in December that Dr. King was going to make a speech in our “lily white” community on March 14. Many were excited by the prospect of the Civil Right leader coming. The Grosse Pointe Human Rights Council was sponsoring the event in an attempt to foster better understanding between blacks and whites. Others clearly opposed his visit. “Why is he coming here to stir up trouble?” I recall one person asking. I’m sure he was not alone in his sentiments.

The chief of police, Jack Roh, was certainly concerned about trouble. His fear was that black militants would use this opportunity to demonstrate, and so he drafted riot control plans. Roh’s concerns were well founded; there was trouble that night. The trouble came, not from black militants as Roh had feared, but from members of an anti-communist white supremacy group called Breakthrough. In order to keep Dr. King safe, Roh actually sat on Dr. King’s lap on the last leg of the trip from downtown Detroit to the high school. Three weeks later Dr. King went to Memphis, TN, where he fell victim to an assassin’s bullet.

As I reflect on Dr. King’s legacy this year, when our nation is in such turmoil, I think Dr. King’s historic visit to Grosse Pointe gives us a number of insights. Allow me to briefly highlight just two.

First, Dr. King was willing to travel to The Other America. That was actually the title of his speech: The Other America. “I use this title because there are literally two Americas,” he said. He was clearly influenced by the report of President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, the so-called Kerner Report commissioned in response to the Detroit riots. That report began with this blunt assessment: “This is our basic conclusion. Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White.” When Dr. King accepted the Grosse Pointe speaking invitation, it meant he, a poor Black southerner, would have to travel to a wealthy northern white community. He had the courage to go to The Other America.

Dr. King’s words remain true today. “There are literally two Americas.” The two Americas in 2022 are different from the two Americas of 1968, but they are just as polarized. We have many ways to describe these two Americas: red states and blue states, Republicans and Democrats, people who watch FOX news and those who watch CNN. Whatever label you give to it, there is no question– we are two nations. The two Americas of 2022, like 1968, don’t understand each other, nurture prejudices against each other, and avoid each other. And, like 1968, we are destroying each other.

King had the courage to go to The Other America. The danger was real. Roh had to sit on his lap to keep him safe. But he made the trip. And he gave a message that is as relevant for the two Americas of 2022 as it was for the two Americas of 1968.

"Let me say finally, that in the midst of the hollering and in the midst of the discourtesy tonight, we got to come to see that however much we dislike it, the destinies of white and black America are tied together. Now the races don't understand this apparently. But our destinies are tied together. And somehow, we must all learn to live together as brothers in this country or we're all going to perish together as fools."

It is tempting to surround ourselves with people like us, people with whom we agree. When we do so, we only reinforce our misconceptions, our misunderstandings, and our prejudices. We all need to make the frightening journey to The Other America, wherever that is. Those who live in urban areas need to spend some time in “flyover country,” drinking coffee and chatting with the locals. Those who live in the heartland need to spend some time in places that are not dependent on agriculture for their economic survival. Every one of us would be both challenged and enriched by developing relationships with people who are from a different background or think differently than we do.

Secondly, Dr. King treated those with whom he disagreed with absolute respect. I had the privilege a couple of years ago to interview an elderly woman who was there that night. She had just one memory of that historic event. “Dr. King was such a gentleman,” she said.

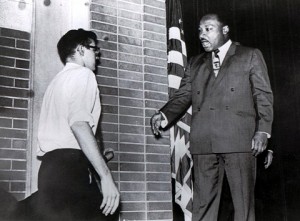

When Dr. King was introduced, the audience gave him a five-minute standing ovation, the first of 32 times they applauded the speaker. But twice during his speech he was interrupted by those who opposed him. The first interruption came from a woman in the audience. “I’ll just wait until our friend can have her say,” King said.

The second disruption came from a young man when Dr. King began speaking of his views on the Vietnam War. “Alright if you want to speak, I’ll let you come down and speak and I’ll wait. You can give your Viet Nam speech now listen to mine. Come right on,” King offered. The young man walked up to the podium and introduced himself. “Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Joseph McLawtern, communications technician, U.S. Navy, United States of America. I fought for freedom I didn’t fight for communism, traitors and I didn’t fight to be sold down the drain. Not by Romney, Cavanagh, Johnson – nobody, nobody’s going to sell me down the drain.” The Civil Rights speaker thanked the young man and continued his speech.

We need to treat those with whom we disagree with absolute respect. We need to allow them to “give their speech” even as we challenge them to “now listen to mine.” And we need to listen when they give their speech– listen to both the content of what they are saying and to their heart that so passionately energizes their position. We need to avoid stereotyping, name-calling, and crude language. We need to learn how to disagree without becoming disagreeable. We need to restore civility to our conversations.

I hope someday, years from now, when an old person is asked about their memories of me, they are able to reply, “He was such a gentleman.”